Artistic Notes from the Memoir of Water

Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord at META Spațiu

Next to being a place of healing and constant changes, water can also be a place of permanence. A natural environment of loss and recovered meaning, where forgotten layers of human existence and excavated remains of collective and personal histories flow alongside each other. The symbolism of water can be approached from many different relevant themes and levels of interpretation, from its ecocritical importance or its geopolitical transformations through the years, to its psychological representation regarding the metamorphoses of the self. Submerged narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord – Eco-cultural tides is an interdisciplinary and intercultural project based on the collaboration of five Romanian and Norwegian artists: Marina Oprea, Cosmin Haiaș, Kristin Bergaust, Alexis Parra (Pucho) and Alex Mirutziu.

The concept of the recent exhibition, Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord is in constant reconfiguration and reinterpretation through the collaboration of the mentioned artists, whose different approaches and techniques split the theme into complex micro-universes, and simultaneously add to its collective web of meanings. As the curatorial statement mentions: “Water is not merely a resource; it is a living entity, a witness, and a storyteller. It carries within its currents the weight of history, the echoes of forgotten voices, and the traces of ecological and cultural transformations. (…) The Danube and the Oslo Fjord, two bodies of water separated by geography yet united by their ecological and cultural significance, serve as the anchoring points for this exploration.” (Stoeac-Vlăduți 2025)[1]

The complexity of water forms is in perfect harmony with the diversity of intermedial practices used by the artists. Marina Oprea’s[2] series of works, Where Lucid Waters Flow (2025) offers a great example of the above-mentioned synthesis of techniques, as this series combines epoxy resin installations with photography and video art.[1] The series examines the duality between the anthropocentric dialogue and natural decay, permanency and change, and preservation and transformation. Even the title offers interesting connotations and associations. It gives us the impression as if the artist would have wanted to allude to the 2018 novel Where the Crawdads Sing written by the American author and zoologist, Delia Owens. The mentioned novel, about a young girl named Kya, who grows up isolated in the marshes of North Carolina, also has a strong ecocritical message, and the themes of life and decay, untouched nature and human intervention have a major impact on the story. “The lagoon smelled of life and death at once, an organic jumbling of promise and decay. (…) She never collected lightning bugs in bottles; you learn a lot more about something when it’s not in a jar.” (Owens 142)[3] These thoughts are ironically displayed in those installations of Oprea, which conserve plant remains, seashell fossils and rocks collected from the shores of Danube River and Oslo Fjord in epoxy resin. In this way they create an interesting hybrid ecosystem on the verge of human and non-human, drawing our attention to many important questions regarding ecology and ethics.

Can we keep the remaining parts of nature unchanged using artificial procedures, or paradoxically, will our intervention lead to changing and manipulating their original forms? Can we create permanence or would that just be the unnatural imprint of having derailed the natural process of decay? These questions greatly illustrate how the process of immortalization is always mixed with some “drops” of loss and frustration because when something is recreated artificially, something natural is lost. The installations are illuminated, which besides adding to their visual impact, can also have conceptual relevance. Perhaps this is connected with the word use of “lucid waters” in the title of the series and creates the possibility of yet another interesting parallel with the Owens novel. One of the book’s main motifs is the image of the “singing crawdads”. From a scientific point of view, this is an intentionally inaccurate statement, which highlights the symbolic meaning behind it, transmitted also by the characters of the story. “»What d’ya mean, where the crawdads sing? Ma used to say that.« Kya remembered Ma always encouraging her to explore the marsh: »Go as far as you can — way out yonder where the crawdads sing.« Tate said, »Just means far in the bush where critters are wild, still behaving like critters.«” (Owens 111) From this excerpt we can deduce that crawdads “sing” only if they can exist unbothered in their natural habitat, and maybe “lucid waters” also flow and glow freely in the environment they came from. In this sense, the use of artificial light illuminating the installations might have an ironic message.

The opposition between conservation and loss has a crucial role in Oprea’s six photographs as well, which were taken at the shores of the Danube and Oslo Fjord. It is worth noting that the little epoxy resin globes with different fossils inside them, which are applied to the pictures, create an intermedial dialogue between the techniques of photography and installation. This can also be important on a conceptual level, because it creates the impression of double conservation, through the two-dimensional, photographic imagery of the landscape and through the globes, which contain preserved elements from the rivers’ surroundings. However, despite the transformation of the view to an out-of-plane, palpable reality, it fails to reproduce the natural environment and temporal dimension of the fossils. Instead, it creates a new way of perception and form of existence, which layers the past into the present, encapsulates the natural in the artificial and recomposes decomposition through art. The photographs and the epoxy resin globes merging into one another can be seen as some kind of visual chronotope[4] of the moment, constructed and constantly reconstructed in the human memory, which simultaneously denies and echoes the inevitability of death.

Another important artwork of Oprea’s series is a video directed by Alexandru Mihai Gheorghe and narrated by Diana Miron, which gives us the opportunity for a peaceful meditation and also deep self-reflection. The “voice” of the running water melts into the quiet whisper of the narrator. In this way, this dance of sounds can symbolize the unstoppable flow of intertwining timelines and the state of constant change. However, the duration of the video (9:58 min) has a twist on the message of letting go, because it ends two seconds before ten minutes, therefore delaying the feeling of fulfilment caused by the continuity and linearity of time. In contrast with the artist’s previously mentioned, static works, this video shows us that some things can only be saved by letting them go and assisting in their transformation.

The need for metamorphoses and the environmental and social changes caused by time are also the major topics of the art of Cosmin Haiaș[5]. His series of installations, Fish and (Micro)chips intertwine the spheres of modern technology and nature, incapsulating the glowing chips in the frames of different organic elements and textures such as straw, hay, rocks and tree branches, thus creating hybrid identities and cyborg spaces, where the artificial and the natural intertwine and complement each other. Haiaș often combines his artistic perspective with his expertise in engineering. In this case, the precisely designed constructions give us an accurate social diagnosis of the present and project a science-fiction-like, but also surprisingly familiar, vision of the future. Microchips aren’t just crucial components of our digital gadgets but are also used for monitoring routines and the habitual patterns of various animal species. On the one hand, the dual significance of these objects shows how modern technology isolates us more and more from our natural habitats. However, on the other hand, it draws our attention to the possibilities of cooperation and collaboration with other species and ecosystems through observing and understanding them better. In addition, these installations can also symbolize the gradual automatization of humans and the virtualization of their everyday lives. This is based on the opposition of the instinctual, intuitive ego represented by the works’ natural frame and the mechanical way of thinking embodied by the microchips. Besides, Haiaș emphasizes the importance and power of art, considering it the only force which can humanize the non-human and, through the ethical dilemmas it raises, can awaken a society that has distanced itself from nature. However, these installations could have a more disturbing, dystopian message as well. as These fossil frames dominated bymicrochips inside them can be interpreted as the only evidence of a lost era coded in those digital archives.

In Kristin Bergaust’s[6] work, compared to Haiaș’s, observation and documentation are not only presented on a symbolic level but also evolve into a complex storytelling technique that seeks to articulate the voice of the Danube. The interdisciplinary strategies of her video essay River of Many Names bridge the gap between an objective approach to historical and geopolitical case studies and the subjective poesis of natural and artificial scenes, which are surrealistically overlaid. This dual perspective is strengthened by the presence of both verbal and visual storytelling methods since the meticulous documentation of the official names in different countries and languages of the Danube is juxtaposed with the river’s past and present told through images. The naming strategies of different people highlight the intercultural and international contexts of the river’s history but also reveal the archive of a natural environment dominated and appropriated by human viewpoints. This is in contrast with the visual attempt to represent the voice of the silenced Danube. The video shows us how the river’s ecosystem is threatened by human activity such as overfishing[7] or contaminating the water with plastic and other hazardous waste and how its water network is disturbed by its artificial environment. It tells us how the dams of the Iron Gates[8] mutilated a section of the Danube into a lake, and how the town of Orșova was submerged 22 metres underwater after a drastic flooding of the river. In this way, it highlights the interaction-based dynamics between human and non-human spaces. Therefore, the video, based on a complex synthesis of different media and genres, conveys the sensitizing and cautionary message of human oppression and the resistance of natural forces against it. In this work, the violent past, the hopeful present and the uncertain future of the Danube flow into each other.

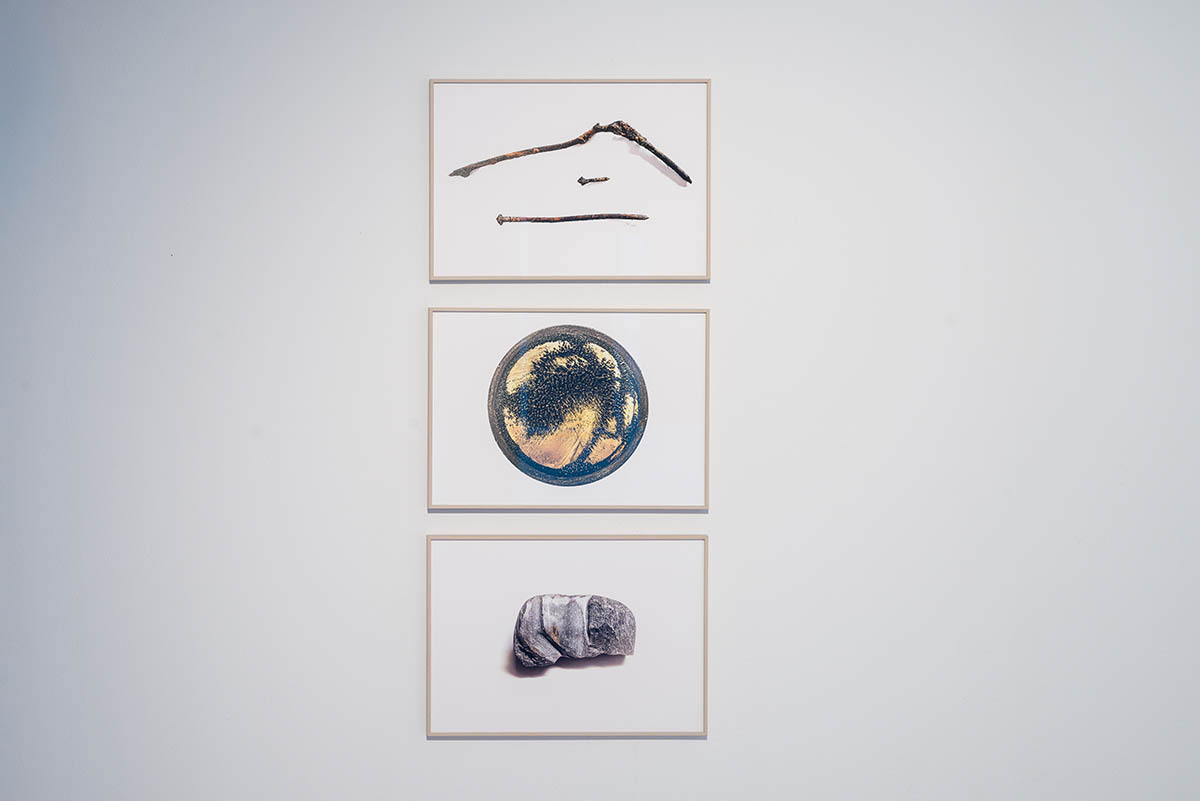

While in Bergaust’s video essay, we could examine how Anthropocene activity affected the river’s water system through the years, in the video of Alexis Parra (Pucho)[9] we can see a different approach to the topic. We can witness how the Danube and the Oslo Fjord wrote and rewrote the collective history and the personal stories of people several times in their “memoirs” of water. Iron becomes an important motif and transmitter of the relationship between human and non-human, which is also the common subject of the three photographs complementing the video. The photos are hung one below the other on the wall; the first one represents iron nails, the second one portrays iron scraps and the third one shows a rock named amphibolite. The pictures are contextualized by postcard-like elements placed near the video, which display the miniature versions of the photos, while on the other side, they have letters written on them addressed to the Danube (“Dear Danube!”).

The first card depicts the iron nails from Eșelnița[10], which serve as a bond and create a dialogue between our inner and outer world, our organism and environment. “Without iron, we have no life. At the core of the planet, Earth is iron, and in all environments and our bodies, we have a balance of iron.” On the second card, there is the following message: “When I fish in the Danube the histories are buried in layers of mud, maybe from communist times, maybe from Roman times or even Stone Age settlements. (…)”. The text refers to Central-Eastern Europe’s layered history buried under the mud, creating a poetical parallel between the “dance” of magnets and iron scraps with our collective past drifting on the waves of the water. On the third card, we can see an amphibolite of which the writer of the letter assumes “it can be a leftover from production of iron”. The curatorial statement refers to Parra as an “archaeologist of water”, who shows us the peculiar relationship between the fragility of human existence broken into different historical eras and the unwavering power of the river, which rushes over every obstacle.

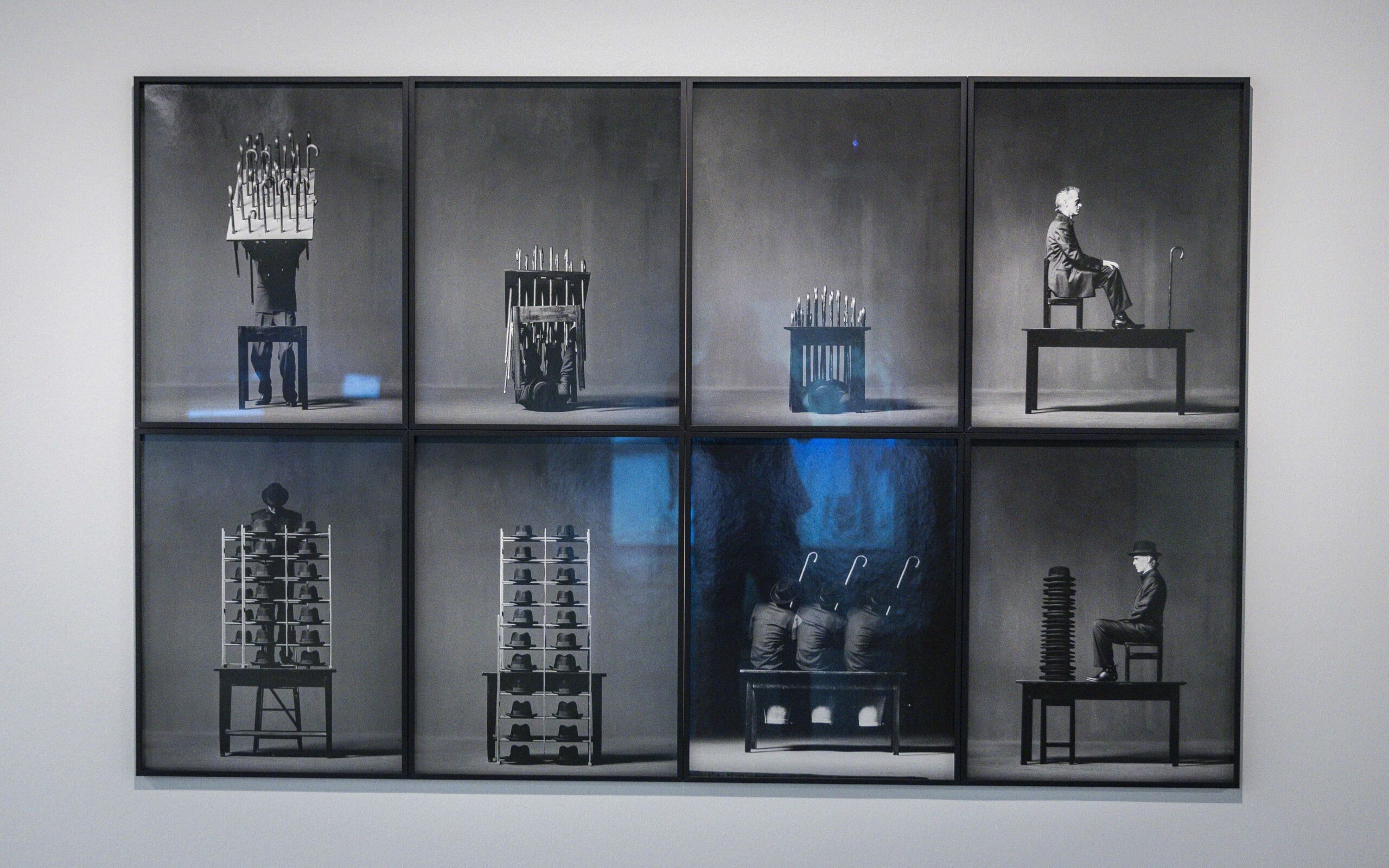

However, water can carry not only ecocritical and geopolitical messages but also complex psychological and philosophical connotations that explore the fluctuating relationship between our self-image and our social perception. Alex Mirutziu‘s[11] movie Dump Cinema (2025) approaches the theme of water through the tension between the desire for self-identification and the conservative dogma that obstructs it. He draws a bold and taboo-breaking parallel between the instinctive nature of homoerotic desire and the liberating irrationality of the undulation of water. This is in contrast to the collective heteronormative indoctrinations which, as artificial cultural constructs, impede the natural need for desire and self-discovery, reacting to it with judgement and stigmatisation. This also distorts the mental patterns of self-image, which may result in shame and sexual abstinence. Mirutziu depicts a tense and painful dance between queer identity and self-acceptance and the sense of guilt and self-hatred, a consuming cognitive dissonance, which, just like water, sometimes flows, inundating us and sometimes dries up. Furthermore, by rethinking the sexual procedure of edging and by postponing conscious ways of interpreting the film, the artist tries to move the viewer away from modes of perception based on conventional codes of decency. The movie also helps to let go of the sense of anxiety associated with marginalized subjects, opening up space for free and instinctive perception. In this way, water becomes a sensual and liberating medium of intimacy and passion, offering a feeling of safety rather than frustration.

Mirutziu’s works are separated from the rest of the exhibition by a curtain, which can be related to the institutional obligation regarding the display of adult content. However, the use of the curtain can also be interpreted symbolically, highlighting the excessive and oppressing censorship in the official social discourse about LGBTQ+ issues. These techniques have a distorting effect on the perception of sexual minorities, which can be better understood only by those who aren’t afraid to look behind the curtain.

The unconventional storytelling strategies used by the artists are inspired by the intuitive creative forces of water. The intercultural and interdisciplinary narratives of the exhibited works flow into each other, remodelling and complementing the pieces’ possible ways of interpretation. The relationship between the creations of these Romanian and Norwegian artists is similar to the bond between the two rivers they represent. Despite the fact that they are geographically separated, they have many ecological, sociopolitical and symbolical parallels, which tell us captivating tales about the past, the present and the future through the memory of water. Some of the artworks show us how the currents of the river have not only partially preserved our history but also rewritten it in certain cases. Others demonstrate the possibilities and contradictions of conserving nature through human intervention. On a metaphorical level, water can also display the contrastive forces of oppression and diversity, artificial social constructs and instinctual self-identification. Moreover, it can also draw our attention to the role of humanity in creating a healthy “dialogue” between modern technology-dominated virtual spaces and our natural environment for a sustainable coexistence in the future. Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord is an exhibition that makes us rethink our relationships with the natural forces, with the perception of space and time, with collective history, with life and death, and with ourselves.

Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord (artists: Marina Oprea, Cosmin Haiaș, Kristin Bergaust, Alexis Parra (Pucho), Alex Mirutziu; curator: Mirela Stoeac-Vlăduți) META Spațiu contemporary art gallery, Timișoara, 2025. 01. 31. − 2025. 03. 22.

Photos: Benjamin Bledea

[1] This bilateral initiative is financed with the support of EEA and Norway Grants 2014–2021 through the National Fund for Bilateral Relations within the RO-CULTURE Programme.

[2] Marina Oprea (b.1989) is an artist living and working in Bucharest. On her webpage the following description can be read about her artistic vision and achievements: “Her works stem from a fascination for observing and deconstructing the ways in which an identity is shaped, be it that of people, places, objects, in relation to the patriarchal society, the art world and/or her own personal stances. Her projects are often collaborative and make use of various artistic mediums such as performance art, ready-made, video, land-art or installations. She has recently garnered interest for all things pertaining to fossils, ruins, remains of long forgotten eras, along with transhumanist theories and speculations on the far-away future. She is part of the artist group Nucleu 0000.”

[3] Owens, Delia. Where the Crawdads Sing. Corsair, 2019.

[4] In literary theory and philosophy of language, the chronotope is how configurations of time and space are represented in language and discourse.

[5] Cosmin Haiaș was born in Oradea in 1968. At the moment he lives and works in Timișoara. On his website he refers to himself and his art in the following way: “I am an artist and an automation engineer. I’m interested in discovering ideas through approaching and combining information technology and technological processes with the artistic creation process, ideas that came in line with the value of humanity. Discovering new means of artistic creation by resorting to technological environments and information technology, allows me to present ideas about moral human values and to criticize the skirmishes of the contemporary society.”

[6] Kristin Bergaust (b. 1957) is educated at the University of Oslo and at National Academy of Fine Art in Oslo. She works as an artist, researcher and educator. She is a professor at the Faculty of Technology, Art and Design in OsloMet, Oslo since 2008. She was formerly professor and head of Intermedia at Trondheim Academy of Fine Arts, NTNU (2001-2008) and artistic director of Atelier Nord media lab for artists (1997 to 2001). As in her short bio is mentioned: “Kristin is one of the pioneers of the self-organized early media art scene in Norway from the early 1990-ies. Her feminist and relational perspectives on contemporary conditions are investigated through performative and technological strategies, sometimes also fed by cultural history or other narratives. Experiments with the communicative and the sensory are inherent both in research and art. Currently, she leads FeLT- Futures of Living Technologies, a three year artistic research project based at OsloMet.”

[7] Overfishing is the main direct threat to the survival of Danube sturgeons.

[8] The Iron Gates were built in 1972 under the Ceaușescu regime on the border between Romania and Serbia.

[9] Alexis Parra (Pucho) was born in Cuba in 1966 and he moved to Norway in 2006. In the Norwegian magazine Nesodden Kunstnere the artist is presented in this way: “He has long experience as a printmaker in silk-screen and lithography as well as in public actions, and has exhibited extensively in Cuba and outside. Since 2004 he has travelled in Europe, Asia and the US and extended his artistic interests to encompass digital photo and video and kinetic sculpture. Through practical projects, Alexis Parra also solved various design tasks. His artistic work often reflects an interest in ecology in a wide sense as well as his experience in moving between cultures.”

[10] Eșelnița is a commune located in Mehedinți County, Romania.

[11] Alex Mirutziu was born in 1981 in Sibiu. On his website we can learn that he: “creates technologies of ephemeral reciprocity. Through his films, sculptures, and performances, the artist confronts the antagonism between desire and its satisfaction through the dissolution of strategic actions. In his works, the artist employs technologies of reuse, deterritorialization, and disruption of the bodily apparatus to identify the crisis of the lived body, prompting the human imaginary to modify reality. In his projects, the premise is that of identity as a problem and a task of transgression. The artist often addresses the theme of the difficulty of dying, exploring the concept of ‘un-selfing’, understood as the responsibility of the individual.”