Everyone Is An Ocean

About Hadal of My Aquarium: an exhibition by Rita Koszorús

In 2021, Rita Koszorús won the Painting of the Year Award, a highly regarded prize in the Slovak art scene. This recognition undoubtedly increased interest in what was already a highly interesting body of work: by now, encounters with Koszorús’ name, paintings and projects are increasingly frequent. Born in 1989 in Slovakia, in the small village of Vlky (Vők), she is currently represented by VILTIN Gallery in Hungary. In Slovakia, her most recent exhibition took place at the Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum, situated on the territory of the Danube River dam in Čunovo (Dunacsún). On this occasion, she managed to pull-off a mature, well-rounded concept in a difficult — somewhat contentious — museum space. As we exit the exhibition, we immediately want to know: what will she do next? In the following text, we try to understand exactly what in Rita Koszorús’ work appeals to so many — including us.

As part of the media attention garnered by the prize, the artist has given quite a few interviews in the past period. Retracing her artistic development, these discussions reveal a singular journey. She initially doubted painting’s legitimacy; she then rediscovered it; by today, she wonders whether her work should be seen as painting at all. In a conversation with Helen Tóth, she explains that she considers herself as a visual artist who remains hard to pinpoint: her work is perhaps ‘not enough’ for painting, but too painterly to be considered as conceptual art.

The constant presence of self-reflection, observation and sensitivity fill what are essentially abstract works with tangible content. The accompanying interviews, the videos produced through various collaborations, the titles and the exhibition texts themselves are all helpful and subtle guides for interpreting and absorbing her works. These elements can hardly be accused of conveying clear (or didactic) messages to the public, but they do add a layer of accessibility by sharing some of the inspiration behind the work and engaging in a specific form of communication. It is a refreshing approach in the context of contemporary art which too often is characterised by navel-gazing or an overtly intellectual approach that keeps many potential viewers at bay.

Koszorús has had a long-standing preoccupation with time, memory and nostalgia. As fundamental elements of human existence, all three can readily elicit a sense of identification. Hadal of My Aquarium (the title of the exhibition presented in Čunovo) refers to what gets deposed within us over time, in hard-to-reach depths. The hadal (or hadal zone) is a trench in the ocean, whose depth makes it difficult to explore: we have only very partial knowledge of these places. The title of the exhibition links these zones with ‘our own aquarium’, a reference to ourselves — infinitely smaller and yet with depths equally vast. To truly know one’s self, it is precisely these depths that must be explored.

Anything can be deposited in one’s hadal zone, but the exhibition brings to the surface the artist’s memories most of all: impressions, objects, forms, phenomena, processes. In an ‘open studio’ video shot during one of the coronavirus lockdowns, Koszorús talks about how she gains inspiration by observing everyday, simple — even banal — things; she makes sketches and recordings, before rearranging these imprints in her paintings, layer by layer. Her images are not photorealistic copies of these objects and phenomena; they are rather highly personal impressions of them, shaped by the subjective processes of memory itself.

Hadal of My Aquarium’s motto is a quote by Virginia Woolf.¹ It reflects on the way our feelings are inseparably linked to the passing of time; the emotions lived in the present will only be fully expressible as time passes. This is not the first time Koszorús refers in her work to modernist literature and the tradition of the psychological novel; Hľadanie Mnémosyné (In Search of Mnémosyné) was the title of her exhibition at Atelier XIII (Bratislava, November 2021-January 2022): a clear reference to Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Both Woolf’s and Proust’s works can be interpreted as imprints of their journeys within their own hadal depths, and Koszorús, by searching for traces of her own life story, places herself in their tradition, Her paintings’s colour palette — as this video shows — is inspired by old photographs linked to the artist’s own childhood in the 1990s. Given the proliferation of a ‘90s aesthetic’ in contemporary cultural production (ranging from films to music videos and fashion) it is perhaps no wonder that these abstract images referencing opaque personal memories make such a strong impression on us.

While their colours and moods are unmistakably moored to our present, Koszorús’s collages place her within two — often opposed — historical traditions. On the one hand, they are in dialogue with the avant-garde practices of the early 20th century, on the other, they perpetuate the craft of painting (a craft whose death has been repeatedly announced!). This mingling of present and past also appears in other forms: instead of the usual artist biography, the exhibition guide for Hadal of My Aquarium contains a text by Koszorús herself. The text begins as most curatorial introductions do (explaining the exhibition’s title, explaining the artist’s intentions etc), before veering into a direction reminiscent of modernist manifestos:

‘[…] I am in search of freedom. I want all of us to feel it. I paint time, I stop time. Real things rarely give me satisfaction: I must invent Reality. I bend images against their limitations. I run to the edge, I want to dive under. But I’m a bad swimmer: I must climb […] I search for disappeared time, I replace time with an oval shape. I don’t want to remember myself. I want to remember myself.’

Despite its evocation of a bygone era, the writing does not feel quaint. It is also understandable why Koszorús feels the need to lean on a historical avant-garde tradition; as she explains in this interview, she finds it difficult to find a place within a Slovak contemporary art scene marked by its lack of abstract tradition. Thankfully, her works do more than merely reproduce the language of a lost time; she challenges it as well. As she indicates in her Secondary Archive² self-description she ‘freely enters’ a discourse that basically links abstraction to rationality and rationality to masculinity with her own personal — and therefore also feminine — perspective.

The manifesto accompanying Hadal of My Aquarium evokes a specific formal language, but also a time when the social impact of art was much stronger than today (or so it seems): a time when society still believed in progress and modernity While much of the contemporary art scene is weighed down by the climate crisis and questions linked to the Anthropocene, social inequalities and possible futures, Koszorús’ texts and paintings — primarily concerned with inner worlds — refer to an era based on a belief in progress. This does not come at the cost of denying reality and its crises. Koszorús’ places an emphasis on a thorough observation of nature; in her works, she does her best to reduce waste and use recycled materials. And yet, her practice does highlight something undeniable. No matter how worried we might be about the fate of our societies, the collapse of the world as we know it, modernity’s last illusions being swept away…as we lay half-awake at dawn or in the dead of the night, chances are high we will be preoccupied with or own memories and emotions: the relevance of looking inwards does not fade.

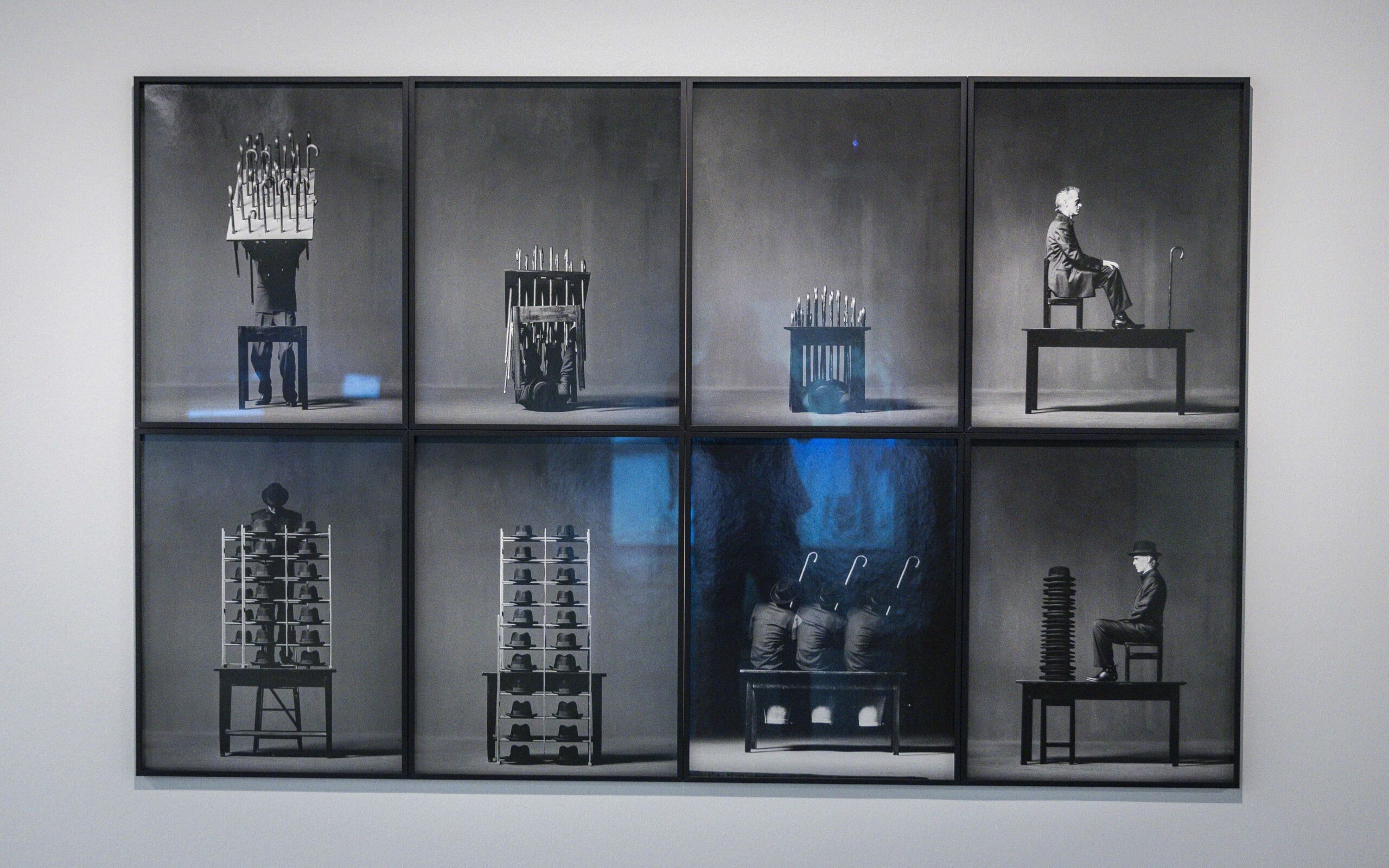

The exhibition at Danubiana features pieces made between 2020 and 2022: works from the schMERZ series — which openly embrace the influence of avant-garde traditions — as well as newer works whose characteristic distinctly depart from earlier pieces. The abstract works have very concrete titles, such as The Vases are Cool Now (2022), I Slept Over in the Studio (2022), Yesterday in Berlin (2022), Hadal of My Aquarium (2022).

In addition to the titles, two videos help interpret the images and installations. Entropia — a piece made in collaboration with Simona Donovalova —offers a number of insights: through close-up nature images, it reveals details that can only be revealed by minute and close observation. It also draws attention to forms, isolated movements and phenomena that appear in Koszorús’ paintings. These show that the abstract forms in her paintings are not some random assortment of lines, but are based on worldly, tangible elements: by helping us perceive and recognise them, the video brings the paintings closer to us.

The other video featured in the exhibition was shot during a residency at Hájovňa in Banská Štiavnica (Selmecbánya) and also focuses on the artist’s method. It shows the importance she gives to spending time in nature and to observation, and her process of recording and rearranging the visual impressions she has gathered. The short film allows us to catch a glimpse into the artist’s methodology and craft. It reveals that she uses airbrushes to apply soft layers atop her paintings, that her creases are real creases and not simply mimesis. As she writes on Secondary Archive, she does not treat the canvas as a surface to be filled, but rather as a textile, using its specific properties — in this case, its malleability — to create an image.

In addition to paintings hung on the wall, the exhibition also features what Koszorús calls ‘spatial collages’: at times, her paintings literally come off the wall. They can lean against each other to form a tent (for example with Home). They can also lean against the wall; static fragments of carpet organically ‘flow’ beneath and between the paintings, stretching, extending the space of the paintings into the space of the museum itself. Crumpled canvases hang on a wooden staircase-like structure: evoking the creative process, they hang as if they had been left out to dry. This illusion of presence — of the artist’s presence — is reinforced by the small sculptures adjoined to the sides of some of the paintings; although not figurative hands, they have presumably been shaped by human hands’ touch. They give the viewer the feeling that someone is holding the canvas from behind — it’s about to move, it will be taken away. The effect is hardly that of a salon-like exhibition, with works gingerly lined up side by side: the hanging itself forms a complex work, a genuine invitation into the artist’s hadal zone. This sensitivity to context is also why we must mention some disturbing factors linked to the exhibition space and which, inevitably, affect the exhibition’s reception.

Opened in 2000, the Danubiana Meulentsteen Art Museum was conceived as a modern art institution whose entire function and form was purportedly designed to support the presentation of art works and exhibitions — i.e. to perfectly fulfil museographic functions. That such a space is inherently discipling and elitist can be debated; either way, that’s the mission Danubiana sets out for itself. The question is whether it actually has the means to fulfil it.

Hadal of My Aquarium is roughly divided across two spaces, half of it in a ship-like space, the other half in something of a narrower corridor adjoined to it. Upon entering, the visitor is greeted by what is a somewhat incomprehensible gesture in the context of an art museum: sentences, seemingly taken from a guest book (?) are displayed on a huge banner. These include quotes such as ‘Danubiana is the most beautiful place in Slovakia’. As one enters the main exhibition space, a larger-than-life portrait of Rita Koszorús and a curatorial text by Barbora Komarová are displayed to the right. To the left, one encounters another cryptical gesture, which – despite having nothing to do with the actual exhibition – also inevitably enters into a dialogue with it. This time, it is a portrait and a glowing tribute to the museum’s founder, Dutch entrepreneur Gerardus Hendrik Meulensteen. These are accompanied by a marble slab (on which the museum’s name is engraved) with a bronze boat atop it. It all brings to mind some historicising-heroic public monument. This marks our entry in the actual exhibition space: Rita Koszorús’ work begins just next to Meulensteen’s iconostasis.

At the centre of the exhibition space, another gigantic banner hangs from the ceiling. It announces good news: the museum has already hosted a million visitors, 200 exhibitions, 1,000 artists from 45 countries. The exhibition does include a large painting by Koszorús herself (its dimensions differ from most of her other works), but its display is dwarfed by the banner trumpeting the museum’s accomplishments.

The corridor-shaped space opens straight into the museum café. Inevitably, café music filters into the exhibition space; inevitably, it becomes part of the experience of looking at the pictures, installation and works. The museum’s inherent (some would say: inevitable) lack of discipline significantly disrupts the visit — or more precisely, it adds lots of unnecessary elements to it. But as I’m writing, I wonder if these aren’t ordinary problems after all, just some elitist grumbling, isn’t the real issue here the space’s symbolic weight and the total absence of critical reflection on it?

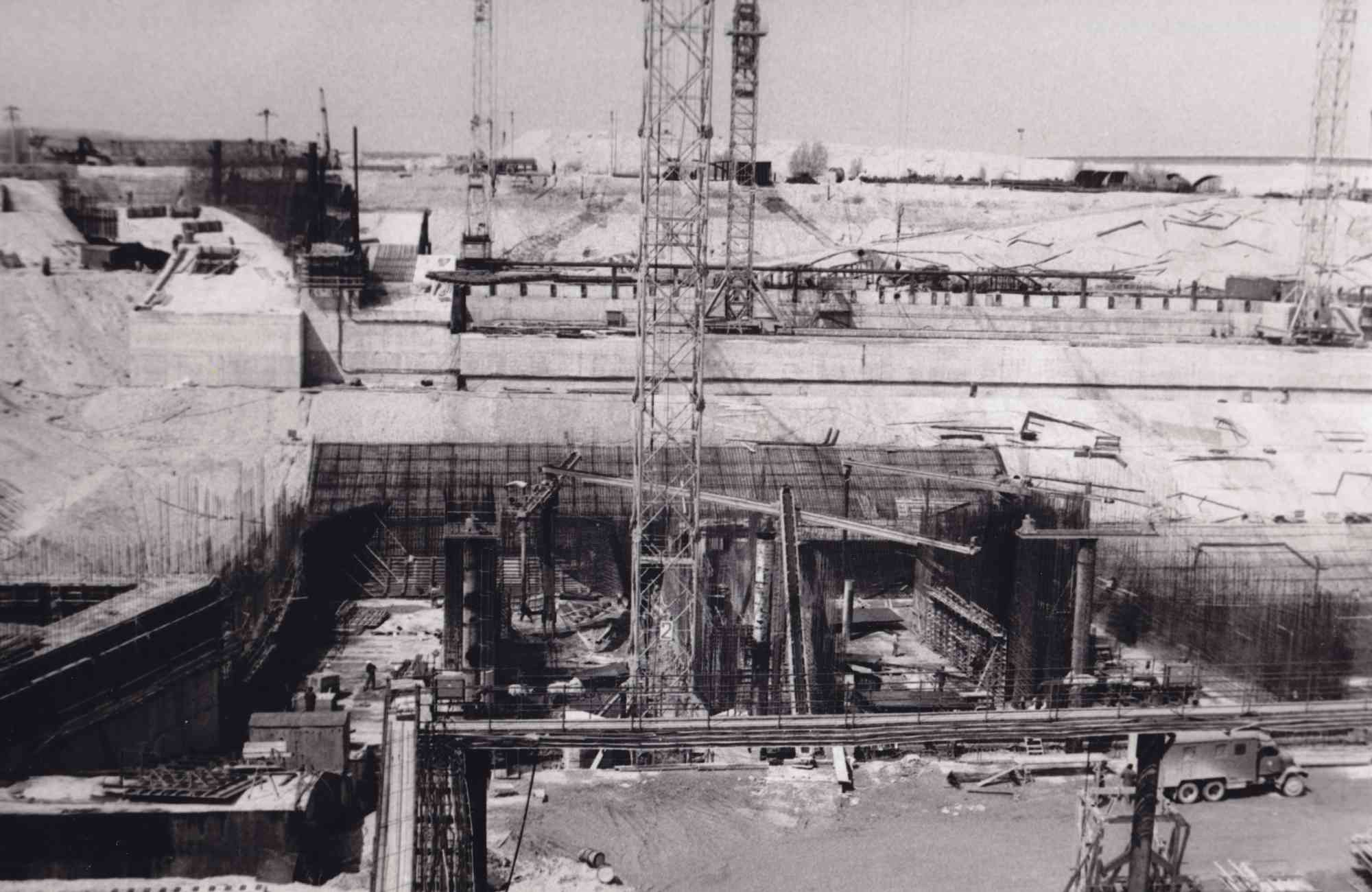

The Danubiana is built on land situated on the territory of the Čunovo dam on the Danube. This is the place where the Danube’s natural bed was artificially swollen in 1992, which enabled the construction of a 40-kilometre-long artificial river between the villages of Čunovo and Sap (Szap), which enabled the Gabčíkovo (Bős) hydroelectric power plant, which all radically transformed the nature and social structure of Žitný ostrov (Csallóköz), an island on the Danube: in other words, it is the location of the biggest environmental wound in the region. What lays today under the artificial river was made up of wetlands, forests, fields, pastures, arable land and inhabited areas. To this day, the Gabčíkovo plant remains a source of open social conflict: there is no consensus on why it had to be built, no consensus on the extent of its environmental cost. The victims of the development – those who lost their lands and houses with little in the way of compensation – continue to feel they have been cheated. Placing a contemporary art museum in a space so fraught with political, international legal, environmental and social conflicts is an inherently risky undertaking. But the Danubiana not only fails to reflect on this situation; it makes no intellectual or artistic effort to formulate its own position towards it. In effect, it remains silent.

The dam — and the so-called ‘New Danube’ which emerges from it— are little more than beds cast in cement. This territory has no organic connection with the land, with the groundwater, its water flow remains tightly regulated by humans. Objects (oftentime carcasses) are filtered out at the Gabčíkovo station, from where the water artificially flows for several kilometres before returning to the Danube’s original bed at Sap. In this sense, the dam and the artificial riverbed are both aquariums: small, closed systems, whose hadal depths the museum makes no effort to engage with. We can note the interesting pairing this forms with Rita Koszorús’ exhibition, in which memory, the act of digging, the symbolism of water, all play such significant roles. Despite its marginal location, the Danubiana is a highly visited institution. This has enabled Koszorús’ work to reach a large audience, which is — whatever the circumstances —a crucial factor in a young artist’s career.

Koszorús Rita: Hadal of My Aquarium, Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum, Čunovo, 10. 09. 2022 – 23. 10. 2022

Translation: Áron Rossman-Kiss

The title of the article is a reference to the song Senki se Tenger (Nobody is the Sea) by the band Gustav Tiger. [1] ‘At the moment I can only note that the past is beautiful because one never realises an emotion at the time. It expands later and thus we don’t have complete emotions about the present, only about the past.’ [2] Secondary Archive is an online archive; it was created with the goal of challenging the lack of visibility of women in the art history of Central and Eastern Europe. The archive includes short biographies and artistic statements of women artists from the region.