The Urge to Play

Julius Koller and Others at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg Group Exhibition

Playing a game can help us strengthen our identity, research, recreate, and socialise, which is not without contradictions during these conflicting times. As we can observe inside the contemporary art world, resistance against socio-political hegemonies can be seen as a driving force behind particular artworks at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg. Presenting the Generali’s collection, the curators (Stefanie Grünangerl, Doris Leutgeb, Marijana Schneider, Jürgen Tabor) extended the term of play with works by Marc Adrian, Josef Bauer, VALIE EXPORT, Harun Farocki, Nilbar Güreş, Hans Haacke, Jürgen Klauke, Julius Koller, Edward Krasiński, Sigalit Landau, Angelika Loderer, Dorit Margreiter Choy, Dóra Maurer, Robert Rauschenberg, Christa Sommerer & Laurent Mignonneau, Franz West.

When visiting the group exhibition Playing Rules!, we can learn how rules and systems operate and what it means to bend and break them. The exhibition is centred around the theme of play in art, offering a retrospective view of specific artists who thematized play, focusing on the body, sports, communication, and media imagery. The potential of play is not only transformative, but essential to tackle the complexities of interdependence, attention, and democracy. Next to improvisation and experimentation, we need to understand that playing by the rules is necessary to understand each other (and the exhibition itself).

Section I. // Open Score

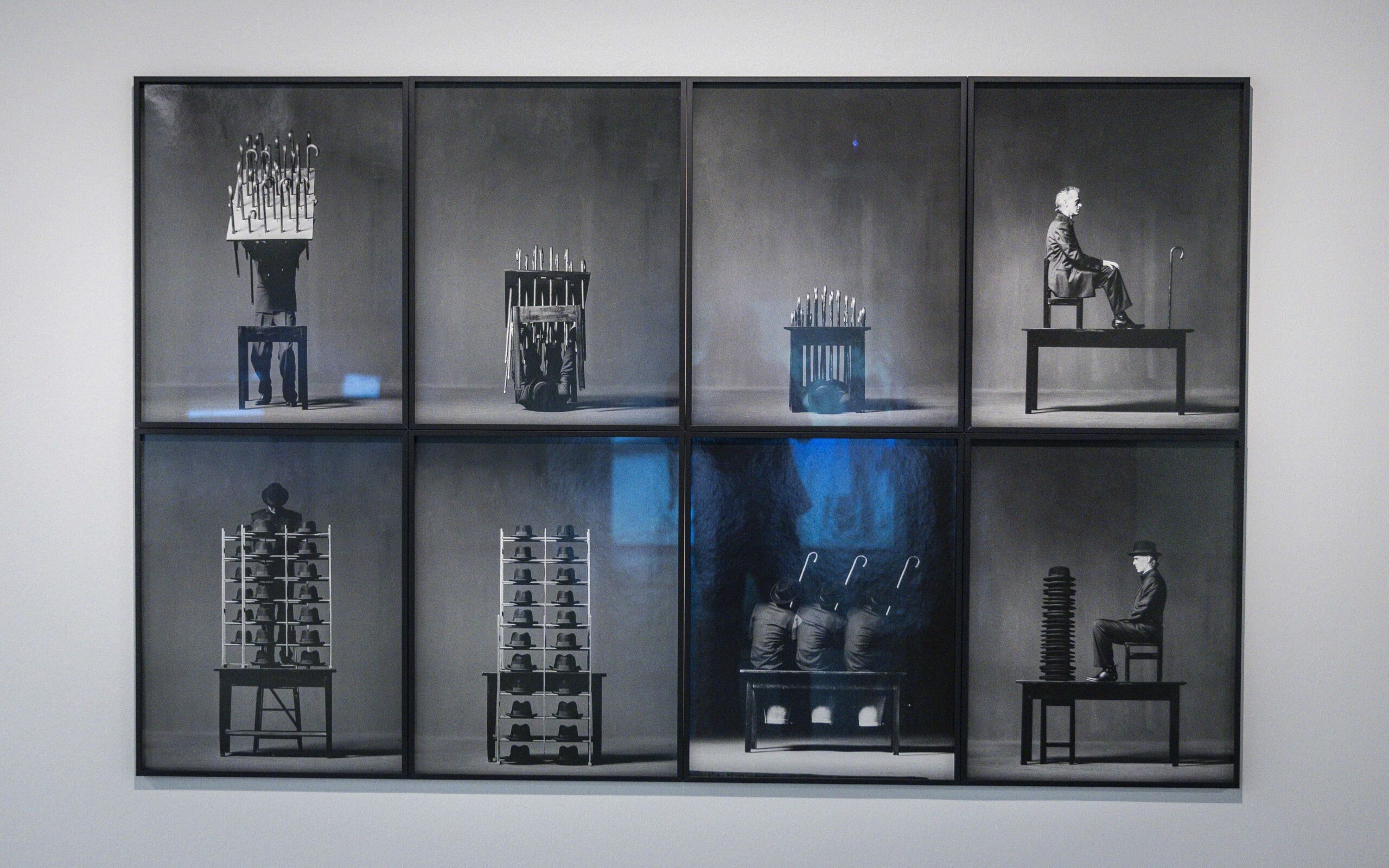

The concepts and practices of open score are presented in the first section of the group exhibition. In the first room, we can find Marc Adrian’s neo-avantgarde “Hinterglasmontagen” (Montages behind glass) which was produced as an interactive object by the artist in 1955. The open score in this case manifests through the open artwork itself: as an interplay of the object and the observer. Via the three artworks of the Hinterglasmontagen, the spectator can encounter a unique optical experience by playing the rules of the artwork itself: due to the different optical rules of the geometrical composition, the spectator can set it in motion while looking at it from different viewpoints. While Adrian constructed the optimal integration of the spectator, he entered into the experimental field of art psychology. The last step of the creative process of the artwork is given to the observer in this sense.

Voyeurism is an often-used term in feminist artworks. Dorit Margreiter Choy’s installation, zentrum (cinéma), 2016 also plays with the position of the observer but from a different perspective, with the deconstruction of the word “cinema”, originating from the Greek word “kinēma” (movement). Just like Marc Adrian, she also builds her concept on optical illusion and the perception of the spectator. The term cinema also anticipates the phenomenon of moving images, which is personally important for Margreiter Choy as a photographer, video, and installation artist.

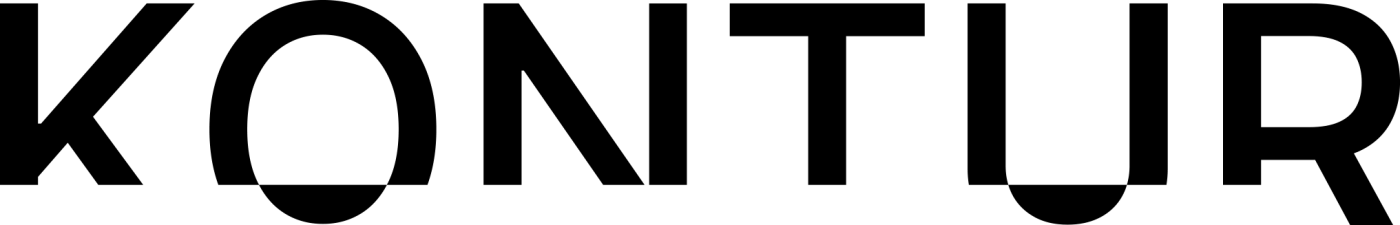

However, what if your viewpoint is stable, but your environment is constantly changing? The German artist Jürgen Klauke plays with everyday objects in his series, called “Sonntagsneurosen” (Sunday neuroses) 1991. It seems that Klauke’s objects have a life of their own, the walking sticks, the chairs, the table, hats, and buckets move around, and they have their own characters in an ironic sense. The objects carry their own meaning, while the visitor cannot be sure where the protagonist (the artist himself) goes.

As Lauren Berlant (the American cultural theorist) wrote, “Cruel optimism is about how people will stay in relation to their object even if it destroys them because they can’t bear giving up the pleasure of knowing the world in a particular way.” Playing with the flaneur’s character, he extends his everyday walks.

In this first room, we can also find the Dóra Maurer’s experimental films and videos. Playing, in her case, meant measuring space, time, and movement. Her performative acts were characterized by formal rigour and the integration of chance events. We must not forget about her background, and how she suffered from the autocratic system in Hungary in the 70’s. Her only way of survival was her underground artistic and pedagogical practice. With her clearly defined rules, she could create her own world and playground, which involved unpredictable elements. Időmérés (Timing, 1973/1980) shows the artist following a given folding pattern, her hands folding a white cloth in front of a black background. In the repetitive sequences, we can find beauty as they turn into a video montage within the Super 8 camera. The artist also uses her own body as a measurement tool in Arányok (Proportions, 1979). Maurer’s choreography follows her own patterns, creating unique poetry on variation. The role of imagination, which was already dominant in the first theoretical art texts in ancient Greece, also became a key concept for Maurer, next to experimentation.

Section III. //Sport as a social metaphor

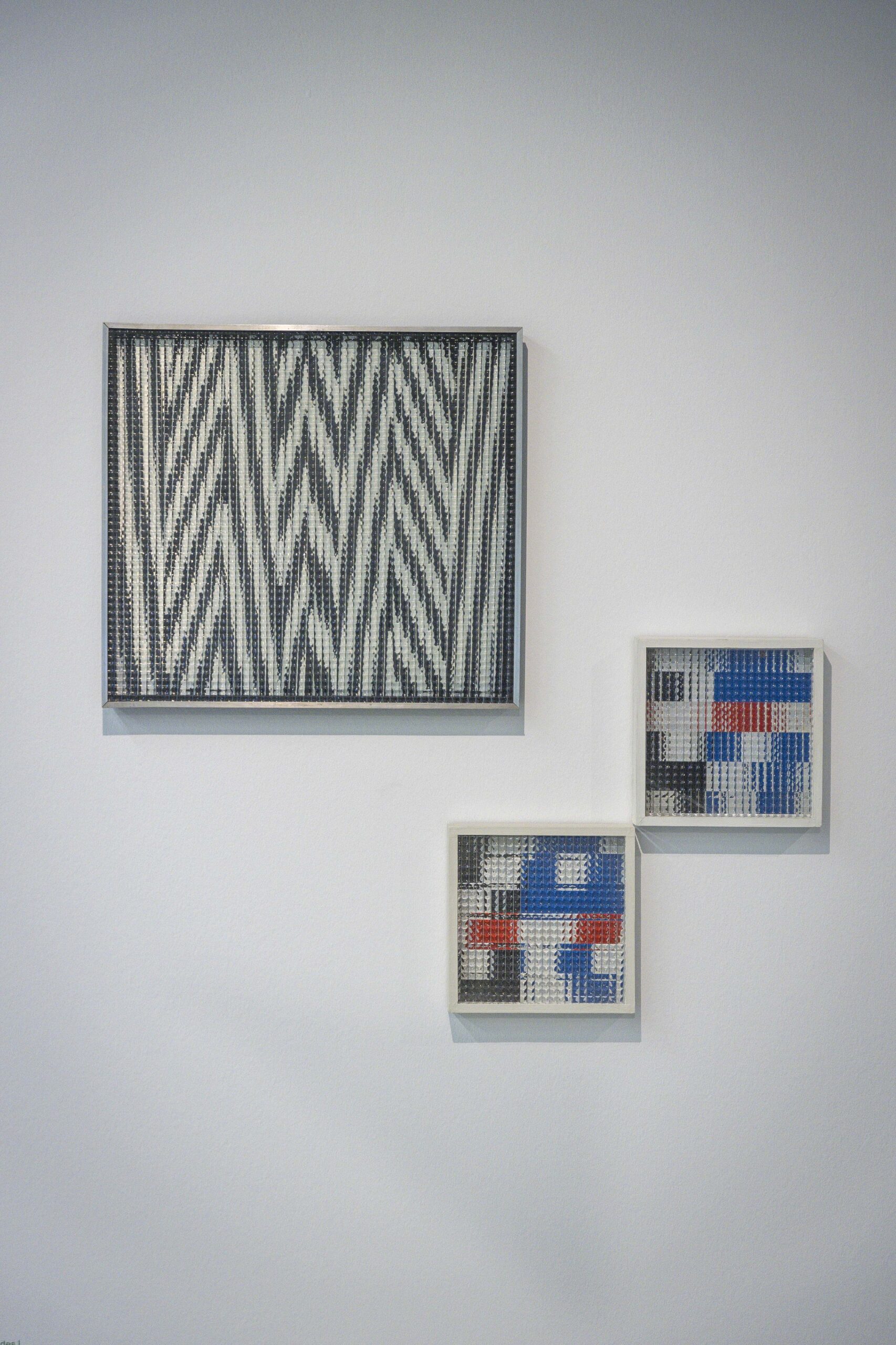

Playing can be a method to construct new transit zones and observe new territories. Play can also be a special way of experiencing the world, as well as enabling you to distance yourself from conflict or other difficult situations. As the curatorial text suggests at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, it can be a metaphor for social coexistence and a driver of cultural transformation. Entering the next section, the first series that grabs our attention is, one of the most important Slovenian artists’, Júlis Koller’s performative play. All the projects exhibited here symbolize democratic communication against hegemony; fair social interactions against repressive political systems. Sport can be seen as a critical stance, especially in Kollers’s projects. Július Koller’s “Anti Happening (Ping Pong)”, 1970–1971, was made during the time of the Prague Spring. Ping-Pong Club, where viewers could play table tennis with Koller for a month-long period, was brought to life in the artwork, now located in the Salzburg Museum der Moderne‘s exhibition room, and deals with the power dynamics of media.

Unsecluded from the era’s political situation, Koller turned the Galéria mladých (Gallery of Youth) into a Ping Pong Club, where everyone was welcome. With his act, he dissolved the boundaries between sport and art, while also making a statement against the end of the democratization process in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR), marked by the events of 1968. From the 1970s, Koller started to use the question mark, and variations of the acronym “U. F.O.” (including “Universal-Cultural Futurological Operations”) to stand against the sense of general resignation during the period of Communist “normalization” in the ČSSR (1972–1989).

The Slovakian artist’s strategy of using everyday objects (just like Dóra Maurer) was a given program of political displacement from the artist’s side. The so-called Cosmohumanist Culture was only one of his main concepts. Putting aesthetics aside and creating a “new cultural situation” was one of his games. His iconic phrase: “Tomorrow is the question”, which could be the slogan of the whole group exhibition, was originally used in his neo-avantgarde participatory work in 1970.

Koller was not the only one who played with Ping Pong. Valie Export’s Ping Pong, 1968 “Expanded Movie”, “Screen Action”, “Film Object”, “Film Action/Action Film”, and “Active Screen” emphasize the politically controlled mass media. No matter how, we, the observers, are active (either on a mental or a physical level). Knowing Export’s style, play can not be seperate from the artist’s body. This installation represents her unique way of thinking.

Section II and Section IV. // Ecological Systems & Interactive Processes, Play as a Social Metaphor

The exhibition has four major sections: the third section explores global and environmental issues, including the Anthropocene (Ecological Systems & Interactive Processes). The most dominant artwork here is Hans Hacke’s well-known transparent cube: Kondensationswürfel (Condensation cube), 1963–1965. Play as a Social Metaphor is the last and largest section, which is divided into two rooms, where we can find artworks that focus on soldiers struggling with the Middle East conflict (Sigalit Landau: Three Man Hula, 1999; Azkelon, 2011) or PTSD syndrome inside post-war and conflict situations (Harun Farocki: Serious Games (2009–2010). Works on the blurring of the conflict between reality and realistic artificiality are predominant in both rooms. As play is often politicized and captured for ideological purposes, the exhibition closes with a question: what options do we have in today’s society to process the events around us?

Playing Rules! The collections (curators: Stefanie Grünangerl, Doris Leutgeb, Marijana Schneider, Jürgen Tabor), Museum der Moderne Salzburg, 15.03.2024 — 20.10.2024

Cover photo: Jürgen Klauke, From the series “Sonntagsneurosen” (Sunday neuroses), 1991, 8 gelatin silver prints on baryta paper, © Museum der Moderne Salzburg, photo: wildbild/Herbert Rohrer

Proofreader: Martha Kicsiny